From June 25th to November 3rd, 2022

In brief

The Mormont hill, a unique place in the Vaud landscape

Halfway between Lake Geneva and Lake Neuchâtel, this rocky promontory linked to the Jura forms the watershed between the Rhine basin, towards the North Sea, and the Rhône basin, towards the Mediterranean.

A geological anomaly, the limestone that makes up the hill has profoundly contributed to the destiny of the place. Since 1953, this limestone has been intensively exploited by a quarry feeding a cement factory.

The Mormont site was the subject of archaeological research between January 2006 and September 2016. During this decade, the total duration of the excavations was 53 months, with a team of 8 to 10 archaeologists. An operation of exceptional scope.

An exceptional site, unique in Celtic Europe

Excavated over a period of 10 years, the Mormont hill has revealed more than 600 structures, three quarters of which are related to the Late Iron Age occupation.

What can be found on the site? Remains of hearths, numerous traces of posts, areas of dumping, and above all several hundred pits, dug into the hillside soil. They contained thousands of still functional objects, but also remains of meals, and multiple human and animal bodies.

Such a variety has no comparison with other Iron Age sites in Europe: the remains of Mormont resemble neither a necropolis, nor a settlement site, nor even one of those architectural sanctuaries known elsewhere in the Celtic world. In view of this singularity, it is in the hundreds of pits that the main key to understanding the site lies.

Pits by the hundreds

Since 2006, 245 deposit pits have been excavated on the site. Each pit contained intentional deposits of various objects.

The analysis of the pits provides concordant information: that the Mormont was used over a short period of time and that the space was managed in a highly organised manner.

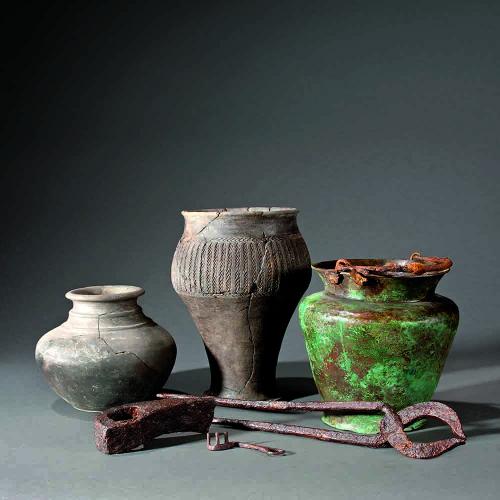

Whether isolated or in clusters, whole or in the form of fragments, the filling of the Mormont pits has yielded a very large number of objects, often very well preserved.

These objects belong to all the categories in use at the end of the Iron Age, with the notable exception of weapons. Thus, culinary utensils, prestigious metal tableware alongside objects of daily life, craftsmen's tools and remains of metallurgical activities, but also ornaments, coins and tokens, associated with animal bones and numerous human bones, are found.

Difficult interpretation

Some objects appear to have been thrown from the top of the pit, while others have been arranged and staged. Some are still in working order, others have been mutilated to make them unusable.

There is thus no systematic practice in the treatment of objects at Mormont. This absence of repetition of the same gestures, which is characteristic of ritual practices, is precisely what is troubling about this site and makes its interpretation difficult.

From a simple burial of waste to a codified ritual practice, how can we perceive the intention behind each deposit from the archaeological remains alone?

Prestigious tableware, ceramics, millstones, metal tools, fetters, jewellery, coins, more than 200 objects are presented in the exhibition, for the first time in France.

The Mormont under the eye of the experts

Once the excavation has been completed, it is time for the analysis. For this, various experts in the field of archaeology were mobilised: restorers, metal specialists, ceramologists, numismatists, archaeozoologists, anthropologists, geologists, etc.

In the case of Mormont, the great variety of remains unearthed and the disconcerting nature of the discovery led to the use of advanced analysis and imaging methods.

These combined approaches attempt to make the most of the information contained in the objects discovered, in order to provide answers to the following questions:

. the period and duration of use of the site (when?)

. on the practices carried out on the site (how?)

. on the identity of the population that created the site (who?)

. the nature and function of the site (why?).

The investigation is still ongoing in 2022. Clarifications have been made on several of these questions, but others remain unanswered.

A multitude of animals

Among the thousands of bones excavated from the Mormont pits, we find the full diversity of domestic livestock from the Second Iron Age: cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, but also horses and dogs. Donkeys and wild animals such as bears, deer and wolves are much more unusual.

Most of the bones of domestic animals show traces of cutting, removal of meat or even cooking with a flame. As is often the case in this period, dogs were also among the dishes!

However, not all animals were eaten. Indeed, some bones bear witness to astonishing selection practices: some forty animals were left whole, some in the form of fresh corpses, others in the form of partially dislocated carcasses after being exposed to the open air for varying lengths of time. And how are we to interpret these bodies of horses, cows and calves that were thrown into the pits, head first or by the hindquarters?

Humans, animals like any other ?

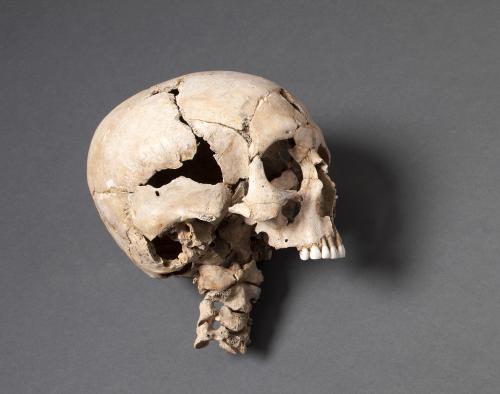

The remains of women, men and children of all ages were found in almost a third of the pits. They include complete bodies, body parts, bodies from which one or more anatomical parts have been removed, and numerous isolated bones. In total, these remains belong to 40 to 50 individuals.

Some of the bodies have been deposited with respectful treatment, reminiscent of a burial. Others adopt surprising positions, on their stomachs or sitting up. A child seems to have been thrown head first into a 4-metre deep pit.

Severed heads, dismembered or broken bodies, or deliberately broken bones are sometimes displayed in association with other types of furniture. Numerous isolated bones are thus mixed with animal remains in the culinary heaps. Two bodies show traces of cutting and exposure to fire, and raise the question of possible anthropophagy.

What can be concluded from this diversity of practices and treatment of human bodies, which is so difficult to interpret? What is interesting at Mormont is the unusual proximity between the treatment of human and animal remains.

What happened on the Mormont?

After ten years of excavations and fifteen years of analysis, are we able to say what happened on Mormont Hill twenty-one centuries ago? The experts were able to answer, in part, two questions: "What?" and "How?

However, many elements remain under debate as to "Who?" and "When?", thus postponing any possibility of ever finding the answer to "Why?

This dossier shows the limits of archaeological research: the buried remains are evidence, but we lack the irreplaceable word of the witnesses.

So, in order to 'tell the story' of their discovery, archaeologists have no alternative but to extrapolate, to invoke analogies with facts proven by ethnological observation, to envisage hypotheses that go beyond what can be demonstrated.

There is thus no univocal vision of the events at Mormont. Everyone, whether an archaeologist, a historian or a curious visitor, has his or her own appreciation, with a multiplicity of points of view commensurate with this exceptional site.

What do you think?

Credits